In South Korea, as nicely, historians say that Carter adopted the messaging of a navy authorities dealing with human rights criticism.

In Could 1980, a student-led pro-democracy rebellion within the South Korean metropolis of Gwangju was met with a brutal crackdown. In a single day, 60 individuals have been killed and a whole bunch injured.

Journalist Timothy Shorrock, who has been reporting on US-South Korea relations for many years, stated that the Carter administration was cautious of shedding a helpful Chilly Battle ally and, due to this fact, threw its weight behind the navy authorities.

He defined the US supported the South Korean management by releasing up navy sources that allowed troops to place down the rebellion.

“Realizing that [military leader General Chun Doo-hwan’s] forces had murdered 60 individuals the day earlier than, they nonetheless believed this rebellion was a nationwide safety menace to the US,” Shorrock stated of the Carter officers.

He added that when a US plane service was despatched to the area, some protesters satisfied of US rhetoric on democracy and human rights believed that the US was coming to intervene on their behalf.

As a substitute, the service had been deployed to bolster the US navy presence in order that South Korean troops on the demilitarised zone with North Korea might be reassigned to place down the rebellion.

Shorrock says that contingency plans even included the doable use of US forces if the unrest in Gwangju unfold additional.

Whereas there isn’t a universally accepted loss of life toll for the rebellion, the official authorities determine is that greater than 160 individuals perished. Some tutorial sources put the loss of life toll at greater than 1,000.

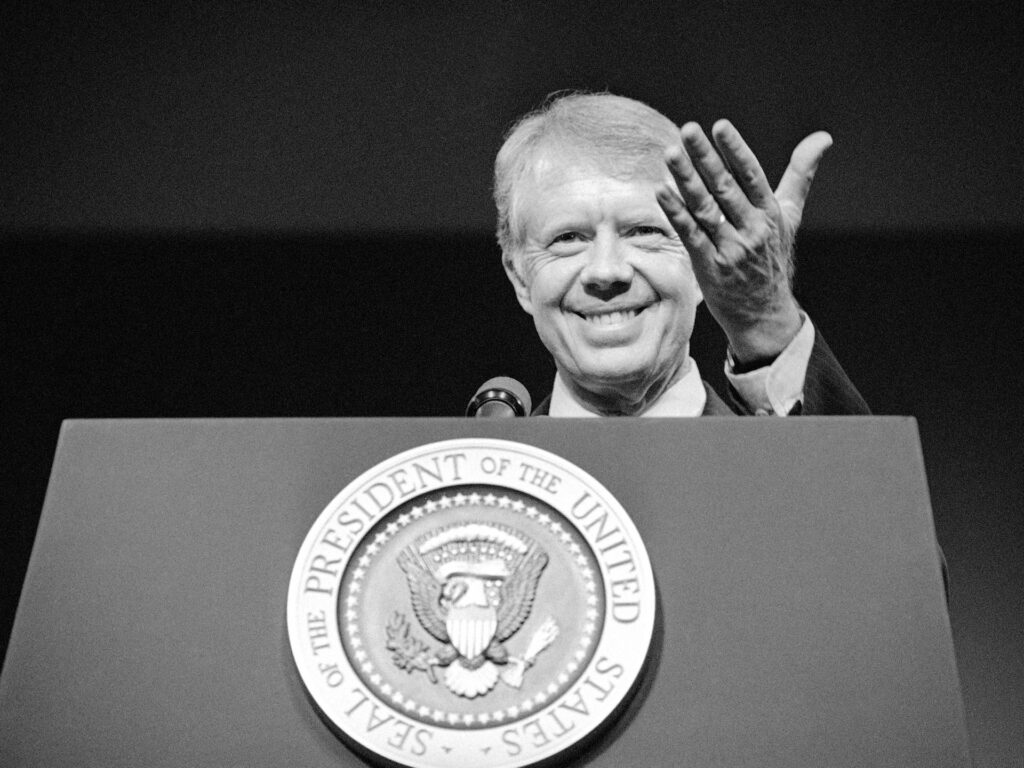

Requested by a reporter if his actions had been at odds together with his professed dedication to human rights, Carter stated that there was “no incompatibility”.

He asserted that the US was serving to South Korea preserve its nationwide safety in opposition to a menace of “communist subversion”, mirroring the rhetoric of the nation’s navy management.

It was the sort of rhetoric that South Korean leaders had lengthy used to justify repressive and antidemocratic measures.

When South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol declared martial law in December 2024 within the title of combating “antistate forces”, many drew parallels to the traumatic occasions of Gwangju.

“What he was saying on the time was what Normal Chun Doo-hwan was saying, characterising this as a communist rebellion, which it was not,” stated Shorrock. “He by no means apologised for that.”